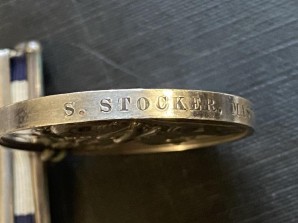

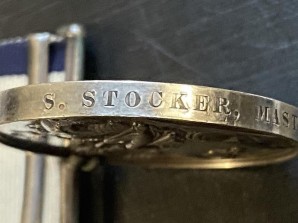

Naval General Service medal – Java (Stephen Stocker, Master’s Mate)

Stock No. 127570

Product Information

Out of Stock

(on consignment ). This man joined the navy and became an officer at the age of 13, saw much action against Privateers, was badly injured falling from a mast, recovered, saw considerable action in the east, against both the French, and Indonesian pirates, finally having quite an interesting time in the Coast-guard, before re-joining the Royal Navy..

Commander Stephen Stocker. (Lieut., 1815. f-p., 36; h-p., 6.)

Born 21st September 1791 in Kenton, Sidmouth, Devon to father Stephen, mother Mary, who were Presbyterian non-conformists. Stephen entered the Navy on 2nd February 1805, at the age of 13 years, on the books as an Able Seaman on board HMS Scorpion. He was the brother of Captain Walter Broad Stocker, R.N.

Scorpion (Brig-sloop 18) 2nd February 1805 – March 1809

Captains Phillip Cartet and Francis Stanfell. On joining he was rated as AB on the ships books, as probably all midshipman positions were filled. However, two months later on 11th April 1805 Stocker was rated midshipman at the age of 13.

Prizes galore

A French naval officer, Commodore Jean-Jacques de Saint Faust, temporarily out of favour following the failure of his mission to launch a diversionary attack on the Shetland and Orkney Islands, had been entrusted with a special mission in the Caribbean. He had been ordered to take an armed schooner DE EER, also known as L’HONNEUR of the Batavian Privateer Company, to Curacao with a special cargo. On arrival he was to assume command of the naval forces of the Batavian Republic. He had been forbidden from taking any prizes on the way out, but once his mission was complete, the vessel could harass British shipping and take prizes on the way back.

Dawn on the 11th April 1805 saw HMS SCORPION operating off the Dutch coast in company with the 14 gun hired armed brig PROVIDENCE and the 10 gun hired armed ship THAMES. The two hired vessels sighted and chased DE EER, which turned and fled, only to encounter HMS SCORPION off Terschelling, to whom she promptly surrendered. Saint-Faust attempted to disguise himself as a seaman, but was found out. An attempt to throw their orders and dispatches overboard was also unsuccessful, when, insufficiently weighted, they were recovered by the British. On examining the cargo hold of DE EER, HMS SCORPIONS men found that the vessel was loaded with 1000 stands of muskets, 2 x 12pdr field guns, 2 mortars and uniforms and tents for 1000 men. HMS SCORPION took DE EER into Yarmouth, from where Saint-Faust was taken to the prison hulks off Sheerness to spend the rest of the war.

On 22nd January 1806, Commander Carteret was promoted to Post Captain, but SCORPION had just sailed to the Leeward Islands station and so it was some time before notification caught up with him. While on the Leward Islands station, he shadowed Admiral Willaumez’s squadron, coming close enough at one point to draw several cannon shots.

In July 1806 Carteret helped Captain Kenneth McKenzie of save 65 deeply laden merchantmen at St. Kitts from destruction. Carteret had sent a letter warning McKenzie that a French squadron under Admiral Willaumez had arrived at Martinique. CARYSFORT and the armed store ship DOLPHIN sailed leeward with their charges and so escaped the French, who had sailed from Fort Royal on 1 July. The French squadron succeeded in capturing three merchantmen at Montserrat and another three and a brig at Nevis; the fort on Brimstone Hill (St. Kitt’s) and a battery on the beach protected nine others that had missed the convoy, though the French did attack them.

Commander Francis Stanfell had been appointed to command Scorpion on Carteret’s promotion. However, he did not succeed in catching up with her until 1807. When Stanfell got to Barbados he found out that she had sailed to the North America station. After waiting some month in Barbados, he received news that SCORPION was back at Plymouth and he sailed to join her. On 3 January 1807 SCORPION, still under the command of Carteret, was chasing a cutter some 15 miles south of The Lizard. HMS PICKLE came on the scene, made all sail, and succeeded in catching up with the quarry, with whom she exchanged two broadsides. Lieutenant Daniel Callaway of PICKLE ran alongside the French vessel and his crew boarded and captured her. The French vessel was the privateer FAVORITE, of 14 guns and 70 men under the command of M. E. J. Boutruche. She was only two months old and had left Cherbourg two days before. Out of her crew of 70 men, the French vessel had lost one man killed and two wounded. PICKLE had suffered two men severely wounded and one man slightly wounded. When SCORPION caught up she took off the 69 prisoners, who she then landed at Falmouth. On 16th February 1807, HMS SCORPION captured the 16-gun French privateer LE BOUGAINVILLE some 12 miles south-west of the Isles of Scilly. She had 16 guns and 93 men and was 23 days out of Saint-Malo. Capturing her took a long chase and a 45-minute running fight during which the privateer lost several of crew killed; SCORPION had no casualties. Before she captured the other two privateers, SCORPION captured several merchant vessels. Captain Carteret was appointed to command the 18pdr armed 38-gun frigate HMS NAIAD and had been replaced in HMS SCORPION by Commander Francis Stanfell. His previous appointment had been as Master and Commander in the armed transport ship HMS GORGON. On 28 July 1807 while now under the command of Stanfell and with DRYAD in company, she captured the Danish ship TRENDE SOSTRE. Then one month later, on 28 August, still with DRYAD in company, she captured the HANNA, and the FLORA. On 4 September SCORPION captured the CARL VON PLESSEN. On 12 September Scorpion captured the MARIANNE. Because SCORPION was abroad, two-thirds of the prize money for MARIANNE and CARL VON PLESSEN was paid to Greenwich Hospital. On 18 September SCORPION captured the CHRISTLE. Also on that day, SCORPION was in company with PLOVER when SCORPION captured the NICHOLINI. Lastly, on 12 October SCORPION captured the Danish ship GERHARD while SATURN and SWIFTSURE were in sight.

She subsequently accompanied Sir John Borlase Warren in pursuit of the enemy to North America.

After returning to home station, on 21 November 1807, it was the turn of the privateer, GLANEUSE, to fall to SCORPION. SCORPION was about 100 miles south of Cape Clear, off the southern tip of Ireland, and Captain Stanfell had disguised SCORPION as a merchantman to lure privateers. That evening Stanfell enticed the French privateer brig GLANEUSE to come within pistol range. GLANEUSE was under the command of Louis Joseph Guinian, and carried 16 guns and 80 men. She was a new vessel, on her first cruise and ten days out of Saint-Malo. She had already taken two vessels: the ALFRED bound for Poole from Newfoundland and the other was a Portuguese schooner.

On 9th December 1806, GLÂNEUR had captured the hired armed tender UNITED BROTHERS, of four guns. In the fight, UNITED BROTHERS had lost two men killed, one being her commander Lieutenant William McKenzie, and one man wounded.36 On this cruise GLÂNEUR had captured two vessels. One was the brig HORATIO, David Mill, Master, which had been sailing from London to Mogadore; the other was the Portuguese ship GLORIA, which had been sailing from Oporto to London. On 3 December 1807 it was the privateer ketch GLÂNEUR’S turn. Stanfell had obtained information from the captured GLANEUSE that enabled him to capture the privateer after a chase of 12 hours. She was under the command of M. Jaquel Fabre and had 10 guns and a crew of 60 men.

GLÂNEUR had been preying on shipping for two years and had been the most successful privateer out of Saint-Malo. British vessels had repeatedly chased her but she had repeatedly escaped by “superiority of sailing”.

SCORPION sailed to the Leeward Islands at the end of 1807 and then returned home in 1808. She then made at least one cruise to the coast of Portugal. On 24th December, SCORPION recaptured the Portuguese vessel, CONDE DE PENICHE. In March 1809, when a ratline gave way, Mr Stocker fell from the main futtock-shrouds onto the deck, badly injuring his right leg.

While on SCORPION Stocker was present at the capture of at least two dozen enemy vessels, so must have received a fair amount of prize money.

Comet (Sloop 18) March 1809 – April 1809

Supernumerary Midshipman. Captain Richard Henry Muddle. For voyage home due to his injury, from which it took him six months to recover before taking a new posting.

Bucephalus (Frigate-Troopship 32) 4th November 1809 – 15th August 1812.

Captains Chas Pelly and Joseph Drury. Master’s Mate on joining. Commanded a boat in the attack upon Flushing.

To the East Indies

Next, he sailed for the East Indies, where he assisted, again in charge of a boat, at the capture of the Mauritius (Ile de France) in 1810, and again in 1811 at the reduction of Java. Passed for Lieut. on 9th June 1811, presumably by a board of Captains at Calcutta.

Java 1811

3rd Aug 1811 the frigates MODESTE, and BUCEPHALUS along with ILLUSTRIOUS arrived at Chillingching, on the coast of Java, where Illustrious disembarked troops for the campaign. Stocker was in command of one of the ship’s boats during the reduction of Java. On 4 Aug 1811 R. Admiral the Hon. R. Stopford, detached the AKBAR, PHAËTON, BUCEPHALUS, and SIR FRANCIS DRAKE to blockade the French frigates NYMPHE and MÉDUSE in Batavia Road. 3 Sep 1811 the French frigates NYMPHE and MÉDUSE departed from Batavia Road, watched and followed by the BUCEPHALUS, who was joined in the chase on the next day by the BARRACOUTA. However, she had disappeared by the 8th. On the 12th the two French frigates turned to attack the BUCEPHALUS, who eventually escaped in shoal water, and by the 13th was out of sight of the French. Stocker was nominated Acting-Lieutenant of the Bucephalus on 17th November 1811. Remaining at Batavia, the BUCEPHALUS had 127 Officers and Men, including her captain, incapacitated from the effects of sickness due to the climate, and when she departed, in April 1812, she had, out of a crew of 264, only 56 men capable of performing duty.

Hecate (sloop 18) 16th August 1812 – 15th March 1814.

Followed Captain Dury as Master’s Mate. Mr Stocker accompanied a highly successful expedition conducted by Captain Jas Bowen of the PHOENIX frigate against the pirates of Palembang, and aided in forming a settlement on the island of Banca.

HMD Hecate

Borneo pirates

In 1812, Pangeran Annam, of Sambas, Borneo, captured the Portuguese ship ‘ COROMANDEL,’ from Calcutta, and also nine seamen of H.M.S. ‘ HECATE,’ who were all either brutally murdered, or retained as slaves after being hamstrung or otherwise maimed. In these depredations the Sambas Rajah was much assisted by the Tampasuk pirates, under the Rajah of Borneo Proper, who could command up to 20 large well-equipped war proas (war canoes), and the captured Portuguese ship.

Retaliation came in June 1813 when Hecate participated in a punitive military expedition against the Sultanate of Sambas. In the HECATE Stocker had command of a boat in a series of arduous operations against the Sultan whose fortifications were destroyed and his piracy ended, although Annam himself escaped in a small sail boat. HECATE sailed for Madras in January 1814. Being ‘Strongly Recommended’ by Captain Drury for his general good conduct, and in particular for his exertions in the attack upon Sambas, a piratical town on the island of Borneo.

Volage (sloop 22) 16th March 1814 – 15th August 1817.

Master’s Mate. Mr. Stocker served with Captains Drury, Henry Warde and John Reynolds in the East Indies cruising off the north coast of Java. Now, for a second time, on 16th March, 1815 he was ordered by Commodore Sayer to act as Lieutenant. Although not at the time aware of the circumstance, he had already been promoted at home by a commission dated 1st of the preceding February. In the early part of 1817 the VOLAGE, while lying at Trincomalee, was hove down on both sides; and for his services on this occasion Mr. Stocker received the thanks of the Commander-in-Chief, Sir Richard King. On Sept. 30th 1816 VOLAGE anchored in Batavia Roads in company with the PROVIDENCE and SOVEREIGN. and several sail of merchant-ships. The BARKWORTH with her consorts remained at Batavia until the 14th of October. From this anchorage they sailed for Indremayo; arrived there the 20th, stayed ten days, and arrived at Semarang on the 4th of November; and departed thence the 11th of November, passing through the Straits of Macassar, and arriving in China (Whampoa) on the 7th of January 1817. VOLAGE finally arrived back in Portsmouth on 24th July 1817 and paid off, with Lieutenant Stocker spending the next 6 years on half pay. On 12th Jan. 1823, he was appointed to the Coast Guard, as a Lieutenant.

Coastguard Service

Chief Officer 12th January 1823 to 11th March 1843.

In command of Swale Cliff Coastguard Station, Kent. He then went on to command various Coastguard stations both in England and Ireland, interspaced with 3 years’ service commanding a revenue cutter.

Dove (Revenue-cruiser) 18th October 1828 to 10th December 1831.

27th Sept. 1828, to the command, for three years, of the DOVE, based at Lyme Regis. On the night of 14th November 1828, the Dove actually snapped three anchor chains in a heavy gale and driven on shore at Bourne Beach. Only with some difficulties were Stocker and his crew saved. After being for a week on shore she was re-floated. Lt. B. Stocker, Chief Officer. removed to Hamble River station on 12 January 1829.

On 28 Jan. 1832, he reverted to a shore appointment. In June 1832 Stocker had a serious run-in with smugglers (see appendix) after they had thrown an officer to his death off the cliff top.

His final station was on the Lyme Cobb, Lyme Regis harbour. (Later to made famous in the film The French Lieutenant’s Woman).

The Cobb, Lyme Regist today, with the Coastguard Station on the left (Now an Aquarium).

When re-posted back to Swale Cliff against his wishes, on 11th March 1843, Stocker resigned his position the Coastguard and applied for a mainstream naval posting. He had served 17 years in command of Coast Guard Stations in both Ireland and England.

Back in the Royal Navy

Stocker’s request to re-join the Royal Navy was granted. He was however not given a sea-going post, being put in charge of Divisions of ships laid out in ordinary at Portsmouth. He was now 52 years old, and more probably suited to a semi-desk job.

San Josef (1st rate 110) 19th July 1843 – 21 May 1845.

Capt. Fred. Wm. Burgoyne. Stocker was placed in charge of a division of the ships in ordinary at Devonport. He was well thought of as an officer, as supporting letters show. Although he tried from promotion before he retired, he was not successful, and had to wait until he could gain the required seniority on the retired list.

Caledonia (1st rate120) 22 May 1845 – 10th August 1846.

Capt. Manley Hall Dixon. Continued to be in charge of a division of the ships in ordinary at Devonport.

Placed on half-pay from 10 August 1846 following 36 years on full pay! In 1851 he lived at Marine cottage, Western Town, Sidmouth, Honiton, Devon.

Marine Place, Sidmouth

He was advanced to Commander on the Retired List on 30th July 1851. He was granted a naval pension on 25th November 1852.

Edinburgh Evening Courant 02 December 1858

In 1861 he was living at 13 Albany Place, Charles the Martyr, Plymouth, with sisters Mary, Elisabeth, Rebecca and Amelia.

Commander Stocker died at 1 Denmark Villas, Grafton Road, Worthing in Sussex, on 21st March 1870 at the age of 79.

Naval & Military Gazette and Weekly Chronicle of the United Service 09 April 1870 Naval & Mil .Gazette etc. 30 March 1870

Appendix.

The following account appeared in ‘King’s Cutters and Smugglers 1700-1855’ by E. Keble Chatterton published in 1912:

On the evening of the 28th of June 1832, Thomas Barrett, one of the boatmen belonging to the West Lulworth Coastguard, was on duty and proceeding along the top of the cliff towards Durdle, when he saw a boat moving about from the eastward. It was now nearly 10 P.M. He ran along the cliff, and then down to the beach, where he saw that this boat had just landed and was now shoving off again. But four men were standing by the water, at the very spot whence the boat had immediately before pushed off. One of these men was James Davis, who had on a long frock and a covered hat painted black.

Barrett asked this little knot of men what their business was, and why they were there at that time of night, to which Davis replied that they had “come from Weymouth, pleasuring!” Barrett observed that to come from Weymouth (which was several miles to the westward) by the east was a “rum” way. Davis then denied that they had come from the eastward at all, but this was soon stopped by Barrett remarking that if they had any nonsense, they would get the worst of it. After this the four men went up the cliff, having loudly abused him before proceeding. On examining the spot where the boat had touched, the Coastguard found twenty-nine tubs full of brandy lying on the beach close to the water’s edge, tied together in pairs, as was the custom for landing. He therefore deemed it advisable to burn a blue light, and fired several shots into the air for assistance.

Three boatmen belonging to the station saw and heard, and they came out to his aid. But by this time the country-side was also on the alert, and the signals had brought an angry crowd of fifty men, who sympathised with the smugglers. These appeared on the top of the cliff, so the four coastguards ran from the tubs (on the beach) to the cliff to prevent this mob from coming down and rescuing the tubs. But as the four men advanced to the top of the cliff, they hailed the mob and asked who they were, announcing that they had seized the tubs. The crowd made answer that the coast-guards should not have the tubs, and proceeded to fire at the quartet and to hurl down stones. A distance of only about twenty yards separated the two forces, and the chief boatman ordered his three men to fire up at them, and for three-quarters of an hour this affray continued. It was just then that the coastguards heard cries coming from the top of the cliff—cries as of someone in great pain. But soon after the mob left the cliff and went away; so the coastguards went down to the beach again to secure and make safe the tubs, where they found that Lieutenant Stocker was arriving at the beach in a boat from a neighbouring station. He ordered Barrett to put the tubs in the boat and then to lay a little distance from the shore. But after Barrett had done this and was about thirty yards away, the lieutenant ordered him to come ashore again, because the men on the beach were bringing down Lieutenant Knight, who was groaning and in great pain.

What had happened to the latter must now be told. After the signals mentioned had been observed, a man named Duke and Lieutenant Knight, R.N., had also proceeded along the top of the cliff. It was a beautiful starlight night, with scarcely any wind, perfectly still and no moon visible. There was just the sea and the night and the cliffs. But before they had gone far they encountered that mob we have just spoken of at the top of the cliff. Whilst the four coastguards were exchanging fire from below, Lieutenant Knight and Duke came upon the crowd from their rear. Two men against fifty armed with great sticks 6 feet long could not do much. As the mob turned towards them, Lieutenant Knight promised them that if they should make use of those murderous-looking sticks they should have the contents of his pistol. But the mob, without waiting, dealt the first blows, so Duke and his officer defended themselves with their cutlasses. At first there were only a dozen men against them, and these the two managed to beat off. But other men then came up and formed a circle round Knight and Duke, so the two stood back to back and faced the savage mob. The latter made fierce blows at the men, which were warded off by the cutlasses in the men’s left hands, two pistols being in the right hand of each. The naval men fired these, but it was of little good, though they fought like true British sailors. Those 6-foot sticks could reach well out, and both Knight and Duke were felled to the ground. Then, like human panthers let loose on their prey, this brutal, lawless mob with uncontrolled cruelty let loose the strings of their pent-up passion. They kept these men on the ground and dealt with them shamefully. Duke was being dragged along by his belt, and the crowd beat him sorely as he heard his lieutenant exclaim, “Oh, you brutes!” The next thing which Duke heard the fierce mob to say was, “Let’s kill the ***** and have him over the cliff.” Now the cliff at that spot is 100 feet high. Four men then were preparing to carry out this command—two were at his legs and two at his hands—when Duke indignantly declared, “If Jem was here, he wouldn’t let you do it.”

It reads almost like fiction to have this dramatic halt in the murder scene. For just as Duke was about to be hurled headlong over the side, a man came forward and pressed the blackguards back on hearing these words. For a time it was all that the new-comer could do to restrain the brutes from hitting the poor fellow, while the men who still had hold of his limbs swore that they would have Duke over the cliff. But after being dealt a severe blow on the forehead, they put him down on to the ground and left him bleeding. One of the gang, seeing this, observed complacently, “He bleeds well, but breathes short. It will soon be over with him.” And with that they left him. The man who had come forward so miraculously and so dramatically to save Duke’s life was James Cowland, and the reason he had so acted was out of gratitude to Duke, who had taken his part in a certain incident twelve months ago. And this is the sole redeeming feature in a glut of brutality. It must have required no small amount of pluck and energy for Cowland to have done even so much amid the wild fanaticism which was raging, and smuggler and ruffian though he was, it is only fair to emphasize and praise his action for risking his own life to save that of a man by whom he had already benefited. But Cowland did nothing more for his friend than that, and after the crowd had indulged themselves on the two men they went off to their homes. Duke then, suffering and bleeding, weak and stunned, crawled to the place where he had been first attacked—a little higher up the cliff—and there he saw Knight’s petticoat trousers, but there was no sign of his officer himself.

After that he gradually made his way down to the beach, and at the foot of the cliff he came upon Knight lying on his back immediately below where the struggle with the smugglers had taken place. Duke sat down by his side, and the officer, opening his eyes, recognised his man and asked, “Is that you?” But that was all he said. Duke then went to tell the coastguards and Lieutenant Stocker on the beach, who fetched the dying man, put him into Lipscomb’s boat, and promptly rowed him to his home at Lulworth, where he died the next day. It is difficult to write calmly of such an occurrence as this: it is impossible that in such circumstances one can extend the slightest sympathy with a race of men who probably had a hard struggle for existence, especially when the fishing or the harvests were bad. The most one can do is to attribute such unreasoning and unwarranted cruelty to the ignorance and the coarseness which had been bred in undisciplined lives. Out of that seething, vicious mob there was only one man who had a scrap of humanity, and even he could not prevent his fellows from one of the worst crimes in the long roll of smugglers’ delinquencies.

30 July 1832 Summer Assizes, Western Circuit, Dorchester, Saturday, July 28.

James Davis and Charles Bascombe were indicted for having, on the 28th June last, at West Lulworth, feloniously assembled, with other persons unknown, armed with fire-arms and other offensive weapons, in order to aid and assist in the running and carrying away of certain prohibited goods – namely, 88 gallons of brandy, which are liable to pay certain dues to the customs. This case excited very great interest here, as the prisoners were supposed to have been in company with, and forming part of the gang of smugglers who attacked Lieutenant Knight and his party, when the former was thrown over a terrific cliff by the smugglers and killed.

List of witnesses etc:

Thomas Barrett Brewer, a commissioned boatman in the West Lulworth Coast Guard – witness

James Lifton – Coast Guard chief boatman at West Lulworth – witness

William Ralph – Coast Guard boatman at West Lulworth – witness

Thomas Teed – Coast Guard boatman at West Lulworth – mentioned by Brewer as being present

Lieutenant Stocker, Chief Officer of the Coast Guard at Osmington-mill station – witness

William Jolliffe, warehouse-keeper at the Custom-house at Weymouth – witness

John Duke, commissioned boatman in the Coast Guard at West Lulworth – witness

Mr. Adamson, Inspector of Police, London – investigating officer – witness

Colonel Rowan – mentioned in evidence

James Carter, coach-guard – witness

The Jury found “Not Guilty” (As the juries were made up of f local men, they regularly sympathised with the smugglers who were also mostly local men who supplied the locality with cheap wine and spirits from the continent – as well as other luxuries.)